What is WannaCry, exactly?

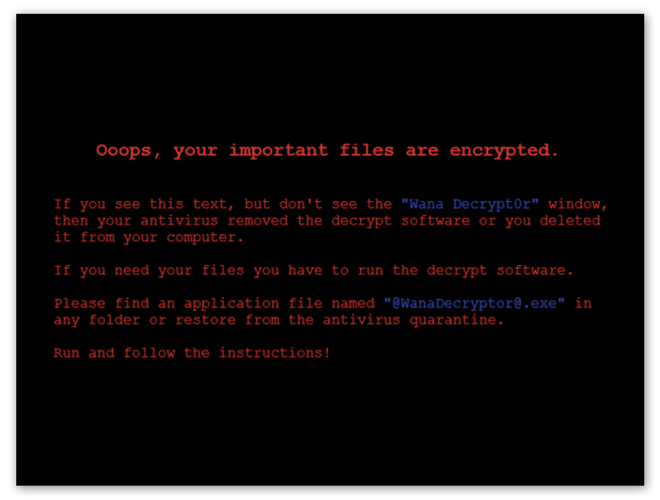

“Ooops, your important files are encrypted.”

Welcome to WannaCry, in which hackers lock up your files and demand payment in order to decrypt them. If you’ve seen this message on your computer, then you’ve either been infected with WannnaCry or a similar form of ransomware.

As the name suggests, ransomware refers to malicious software that encrypts files and demands payment — ransom — in order to decrypt them. WannaCry remains one of the most well-known strains of ransomware out there. Why? Well, there are a few reasons why WannaCry is so notorious:

-

It’s wormable, meaning it was able to spread between computers and networks automatically (without requiring human interaction).

-

WannaCry relied on a Windows exploit that made millions of people vulnerable.

-

It resulted in hundreds of millions (or even billions) of dollars in damage.

-

The ransomware strain spread fast and furiously, only to be halted just as quickly.

-

Its catchy (and apt) name also made it memorable; wouldn’t you wanna cry too if you found all your important files locked up?

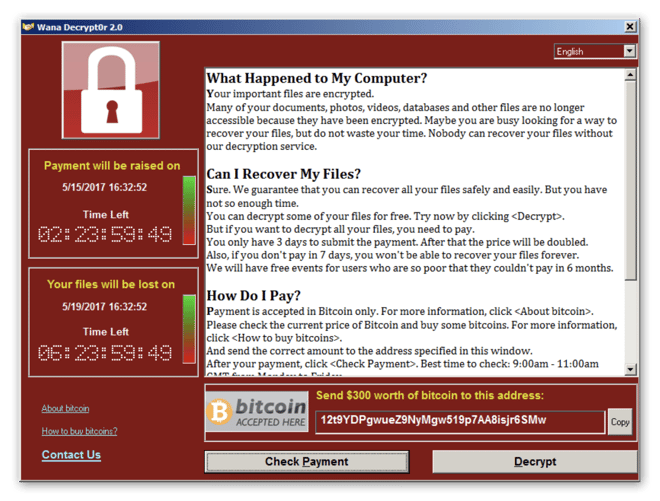

Cybercriminals charged victims $300 in bitcoin to release their files. Those who didn’t pay in time faced doubled fees for the decryption key. The use of cryptocurrency, in conjunction with its wormlike behavior, earned WannaCry the distinction of a cryptoworm.

The WannaCry attack exploded in May 2017, nabbing some notable targets such as the UK’s National Health Service. It spread like wildfire, infecting more than 230,000 computers across 150 countries in just one day.

How does WannaCry spread?

WannaCry spread using the Windows vulnerability referred to as MS17-010, which hackers were able to take advantage of using the exploit EternalBlue. The NSA discovered this software vulnerability and, rather than reporting it to Microsoft, developed code to exploit it. This code was then stolen and published by a shadowy hacker group appropriately named The Shadow Brokers. Microsoft actually became aware of EternalBlue and released a patch (a software update to fix the vulnerability). However, those who didn’t apply the patch (which was most people) were still vulnerable to EternalBlue.

WannaCry targets networks using SMBv1, a file sharing protocol that allows PCs to communicate with printers and other devices connected to the same network. WannaCry behaves like a worm, meaning it can spread through networks. Once installed on one machine, WannaCry is able to scan a network to find more vulnerable devices. It enters using the EternalBlue exploit and then utilizes a backdoor tool called DoublePulsar to install and execute itself. Thus it’s able to self-propagate without human interaction and without requiring a host file or program, classifying it as a worm rather than a virus.

Where does WannaCry come from?

Though it’s not 100% certain who made WannaCry, the cybersecurity community attributes the WannaCry ransomware to North Korea and its hacker arm the Lazarus Group. The FBI along with cybersecurity researchers found clues hidden within the background of the code that suggested these origins.

The May 2017 WannaCry attack

The WannaCry attack began on May 12, 2017, with the first infection occurring in Asia. Due to its wormable nature, WannaCry took off like a shot. It quickly infected 10,000 people every hour and continued with frightening speed until it was stopped four days later.

The ransomware attack caused immediate chaos, especially in hospitals and other healthcare organizations. Britain’s National Health Service was cripled by the attack, and many hospitals were forced to shut down their entire computer systems, disrupting patient care and even some surgeries and other vital operations.

Who did it target?

Though WannaCry did not appear to target anyone specifically, it spread quickly to 150 countries, with the most incidents occurring in Russia, China, Ukraine, Taiwan, India, and Brazil. A variety of different individuals and organizations were hit, including:

-

Companies: FedEx, Honda, Hitachi, Telefonica, O2, Renault

-

Universities: Guilin University of Electronic Technology, Guilin University of Aerospace Technology, Dalian Maritime University, Cambrian College, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, University of Montreal

-

Transport companies: Deutsche Bahn, LATAM Airlines Group, Russian Railways

-

Government agencies: Andhra Pradesh Police, Chinese public security bureau, Instituto Nacional de Salud (Colombia), National Health Service (UK), NHS Scotland, Justice Court of Sao Paulo, several state governments of India (Gujarat, Kerala, Maharashtra, West Bengal)

The attack took advantage of companies running old or outdated software. Why didn’t these organizations apply the patch? Firms like the NHS have a hard time shutting down their entire system to update when they need things like patient data available at nearly all times — though not taking the time to update caused them much more grief in the long run.

How was it stopped?

Cybersecurity researcher Marcus Hutchins discovered that after WannaCry landed on a system, it would attempt to reach a particular URL. If the URL wasn’t found, the ransomware would proceed to infect the system and encrypt files. Hutchins was able to register a domain name to create a DNS sinkhole that functioned as a kill switch and shut down WannaCry. He had a tense few days during which hackers attacked his URL with a Mirai botnet variant (attempting a DDoS attack to bring down the URL and kill switch).

Hutchins was able to protect the domain using a cached version of the site that could handle higher traffic levels, and the kill switch held fast. It’s unclear why the kill switch was in WannaCry’s code and whether it was included accidentally or if the hackers wanted the ability to halt the attack.

How much did WannaCry cost?

Though WannaCry demanded $300 in bitcoin (or $600 after the deadline passed) from a single user, the costs in damages were far higher. About 330 people or organizations made ransomware payments, which totaled 51.6 bitcoins (worth approximately $130,634 at the time of payment). That was the amount paid to the hackers, but the real cost of WannaCry was much greater.

Due to the large amount of government agencies, universities, and healthcare organizations that were ensnared by WannaCry, along with the resulting damage control, the cleanup costs were staggering. Cyber risk modeling firm Cyence estimated the cost at up to $4 billion.

Is WannaCry still active?

WannaCry has not been completely eradicated, despite the kill switch that managed to halt the May 2017 attack. In March 2018, Boeing was hit but was able to contain the damage quickly. Other attacks remain possible. Not only that, other strains of ransomware that utilize the same Windows vulnerability have been developed, such as Petya and NotPetya. Remember, Microsoft has issued a patch (security update) that closes the vulnerability — thus blocking the EternalBlue exploit — so make sure your software is up to date.

How to recognize WannaCry

While other kinds of malware try to hide sneakily on your system, if you get ransomware, you’ll be able to recognize it immediately. There’s no more obvious sign or symptom than a giant screen popping up and demanding a ransom. WannaCry looks like this:

Can WannaCry be removed?

As with all malware, WannaCry ransomware removal is possible — but undoing its negative effects is trickier. Removing the malicious code that locks up your files will not actually decrypt those files. For all strains of ransomware, Avast does not recommend you pay the ransom to unlock your files. There’s no guarantee that you’ll actually receive a decryption code if you pay (remember, these are criminals we’re dealing with). Even if the hackers do plan to send the key, paying the ransom validates their tactics, encourages them to continue propagating ransomware, and most likely funds other illegal activities too.

Some cybersecurity researchers believe that WannaCry was actually a wiper — meaning that it wiped your files rather than encrypting them, and that the authors had no intention of ever unlocking anyone’s files. There were also implementation issues in the payment process: they provided the same three bitcoin addresses to all victims, making it nearly impossible for them to properly track who had actually paid.

So what can you do about locked-up files? You may get lucky and find a decryption tool online. Avast and other cybersecurity researchers decode ransomware and offer the decryption keys online for free. Not every strain of ransomware is able to be cracked, however. In the case of WannaCry, there is a decryption key available, but it may not work for all computer systems.

If you’re not able to decrypt your files, you can reinstate an earlier backup of your system that contains your normal files. But you still need to remove the actual malicious code first. See our guides to remove ransomware, no matter which device you use.

How to protect yourself against WannaCry and similar ransomware strains

While WannaCry is no longer propagating its tear-inducing misery, there are plenty of other ransomware strains out there. Our tips will protect you against current and new ransomware strains, along with other kinds of malware too. You’ll want to defend your system against ransomware, as well as your network and any devices connected to it. Here’s how to prevent WannaCry and other ransomware from getting onto your device:

Keep your software up-to-date

Even though Microsoft patched the EternalBlue vulnerability, millions of people didn’t apply the update. Had they updated, WannaCry wouldn’t have been able to infect them. So it’s absolutely crucial to keep all of your software updated. It’s also important to update your security software (though if you use Avast's anti-malware software, you’re all set — we update our antivirus automatically!).

Avoid opening emails from unknown senders

There are tons of scams out there, and email remains the most popular delivery method for cybercriminals. You should be wary of emails from unknown senders, and you should especially avoid clicking on any links or downloading any attachments unless you’re 100% sure they’re genuine.

Watch out for infected websites

Malvertising, hiding infected ads within pop-ups or banners, is lying in wait on many websites. Make sure to verify that a website is safe before you use it, especially for any kind of shopping or streaming.

Regularly backup all important data

If you have all of your files backed up, ransomware loses its power: you can simply remove the malware and then restore your system to an earlier version without the infection. You should regularly back up all your important documents and files so you’ll always have a clean version of them you can use should they become encrypted. It’s best to save your data in both the cloud and with physical storage, just in case.

Effective defense against WannaCry

Applying software updates as soon as they’re released and using sensible browsing, emailing, and downloading habits can go a long way to keep you safe online — but they’ll never be 100%. Even the most internet-savvy users have occasionally clicked on something by accident or fallen for a clever phishing scam.

That’s why everyone should have a last line of defense protecting you against ransomware, malware, and other security and privacy threats. Avast One stops ransomware like WannaCry in its tracks with our six layers of protection and AI-powered cloud system. Download Avast today and never get your files taken hostage.